Tiny Bugs, Giant Consequences

A deep dive into three of the most infamous software bugs in history—Therac-25, the Patriot Missile and the Mars Climate Orbiter—and the lessons they teach us.

Software rarely collapses from a single line of bad code. It collapses when human factors, missing interlocks, silent UIs, and untested assumptions amplify that code. In what follows, we’ll look at three real incidents—Therac-25, the Patriot missile time drift, and the Mars Climate Orbiter to see how the smallest of digital errors can have the largest of real-world consequences.

Case Study: Malfunction 54: The Error Code That Became Lethal:

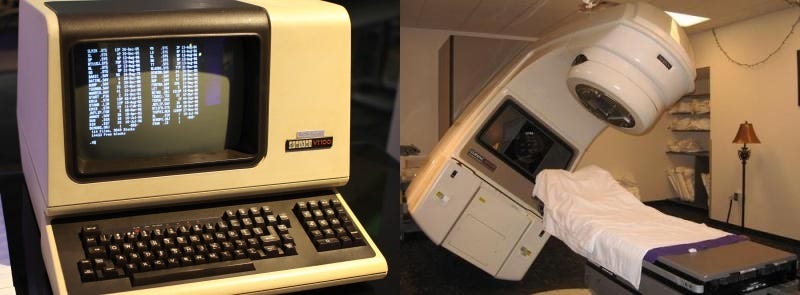

Between 1985 and 1987, a state-of-the-art radiation therapy machine called the THERAC-25 delivered massive overdoses of radiation to at least six patients, with fatal consequences. The story of why this happened is a perfect lesson in how a simple software bug can turn deadly when safety is overlooked.

The Root Cause: The Hidden Software Bugs

Deep inside the machine’s code, two critical flaws were waiting to happen. What made them so deadly was that the Therac-25 was designed to rely completely on software—older models had physical safety locks that would have prevented these accidents, but they had been removed.

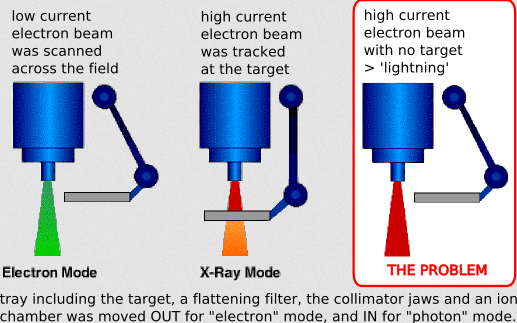

Demonstration of what happened

1. The “Too Fast” Bug (Race Condition): The machine had two modes: a gentle, low-power Electron Beam and an X-Ray Beam over 100 times more powerful that required a metal shield to be in place. If an experienced operator made a mistake while typing and corrected it in under 8 seconds, a flaw would occur:

- The screen would show the safe, low-power setting.

- But the machine’s hardware was still primed to fire the full-power X-ray beam without the shield.

The software never double-checked to make sure the screen and the hardware were in sync.

2. The “Rollover” Bug (Integer Overflow): A counter in the software kept track of adjustments the operator made. But the counter was tiny—like a car’s odometer that can only go up to 255 before it rolls over back to 0.

The programmers made a fatal mistake: they used the number 0 as the “All Clear, safe to fire!” signal.

If an operator made just enough adjustments for the counter to roll over from 255 back to 0, the software would mistakenly think “zero means it’s safe!” and fire the beam without any safety shields in place. This specific bug was responsible for the final documented overdose.

How a Bug Became a Disaster: The Chain of Failures

These bugs created the danger, but a series of terrible design choices is what allowed them to become fatal.

A recreation of the Therac-25’s fatal software flaw

- The Warning Was Useless: When the machine entered a dangerous state, it didn’t flash a red “DANGER” sign. It just displayed a cryptic message like “Malfunction 54.” The operator’s manual didn’t even explain what this meant.

- Operators Were Trained to Ignore Errors: The machine was so unreliable that it would show dozens of these meaningless errors every day. Operators learned that the “fix” was always the same: just press ‘P’ to Proceed. The machine essentially allowed them to override a fatal error with a single, routine button press.

- The Manufacturer Denied the Problem: When hospitals reported the first horrific injuries, the manufacturer, AECL, insisted their machine was perfect and that an overdose was “impossible.” This denial meant that critical fixes were delayed while more patients were put in harm’s way.

In the end, the Therac-25 tragedy wasn’t just about bad code. It was a failure of design, safety, and responsibility that serves as a chilling reminder of what’s at stake in the world of software.

Case Study: The 600-Meter Miscalculation:

In 1991, during the Gulf War, an American Patriot missile battery failed to intercept an incoming Iraqi Scud missile. The Scud struck a U.S. Army barracks, killing 28 American soldiers and injuring around 100 others. The investigation that followed uncovered a shocking cause: the failure wasn’t due to enemy jamming or a mechanical fault, but a tiny, accumulating error in the system’s software.

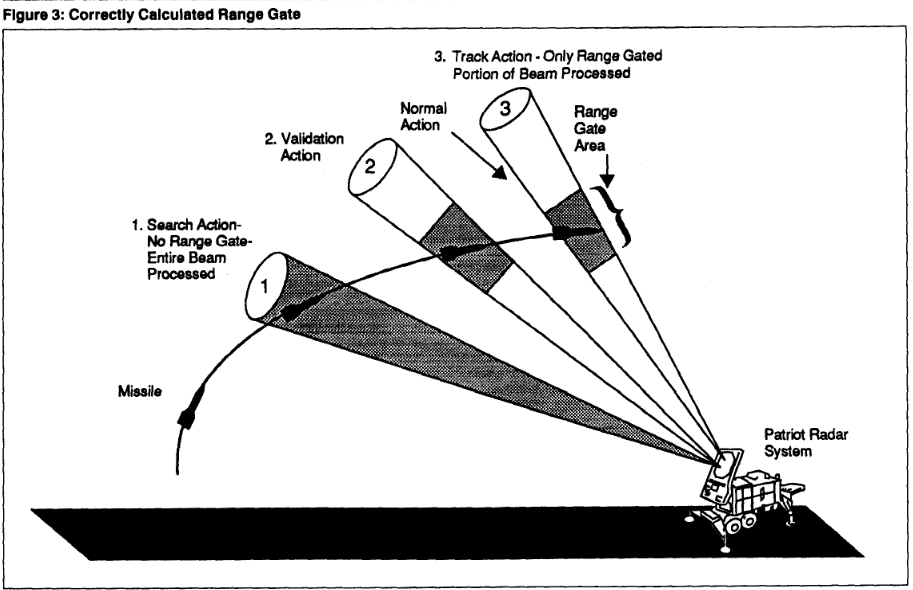

This is how the Patriot Radar System is supposed to work.

The Root Cause: A Flaw in Binary Math

The Patriot system’s software was designed to track time from the moment it was turned on. Its internal clock ticked every one-tenth of a second. Here’s where the problem started:

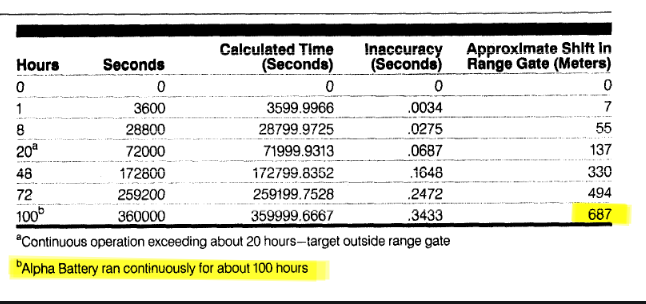

- The Decimal-to-Binary Problem: The number

1/10is simple for us to write as0.1. However, in the computer’s native language of binary (base-2), the number0.1becomes an infinite, repeating fraction. - The Truncation Error: The system’s computer could only store a finite number of bits for this value. So, it had to “chop off” (truncate) the end of that repeating fraction. This created a microscopic error of about 0.000000095 seconds with every tick of the clock.

This tiny error, a result of how computers represent decimal numbers, was the root cause of the failure.

How a Microscopic Error Became a Catastrophe

By itself, an error that small is completely insignificant. However, the danger of floating-point errors lies in their ability to accumulate over time.

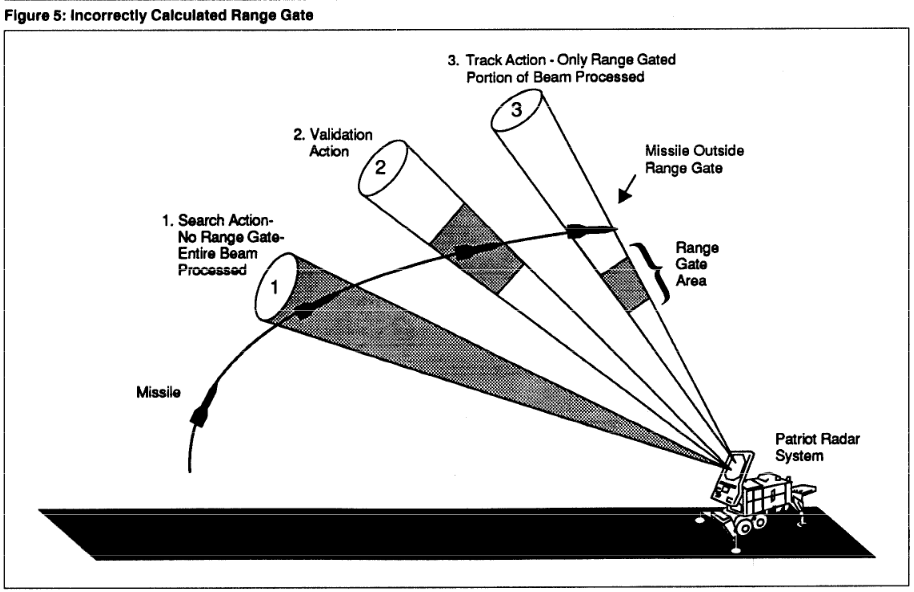

- The Accumulation: The Patriot battery had been running continuously for over 100 hours. Every tenth of a second for 100 hours, that tiny error was added to the clock’s total time.

- The Drift: After compounding for over 100 hours, the accumulated errors caused the system’s internal clock to be wrong by approximately 0.34 seconds.

To a person, a third of a second is nothing. But to an air-defense system tracking a target moving at nearly 6,000 km/h, it’s a massive gap. The system correctly detected the Scud missile, but because its internal clock had drifted, its calculation of the target’s future position was flawed.

The final prediction of where the Scud would be was off by over 600 meters. The system looked for the target in the wrong patch of sky, concluded there was no threat, and its interceptor never launched. A microscopic software rounding error, accumulated over time, led directly to a catastrophic failure.

Case Study: The Unit Error That Destroyed a Mission:

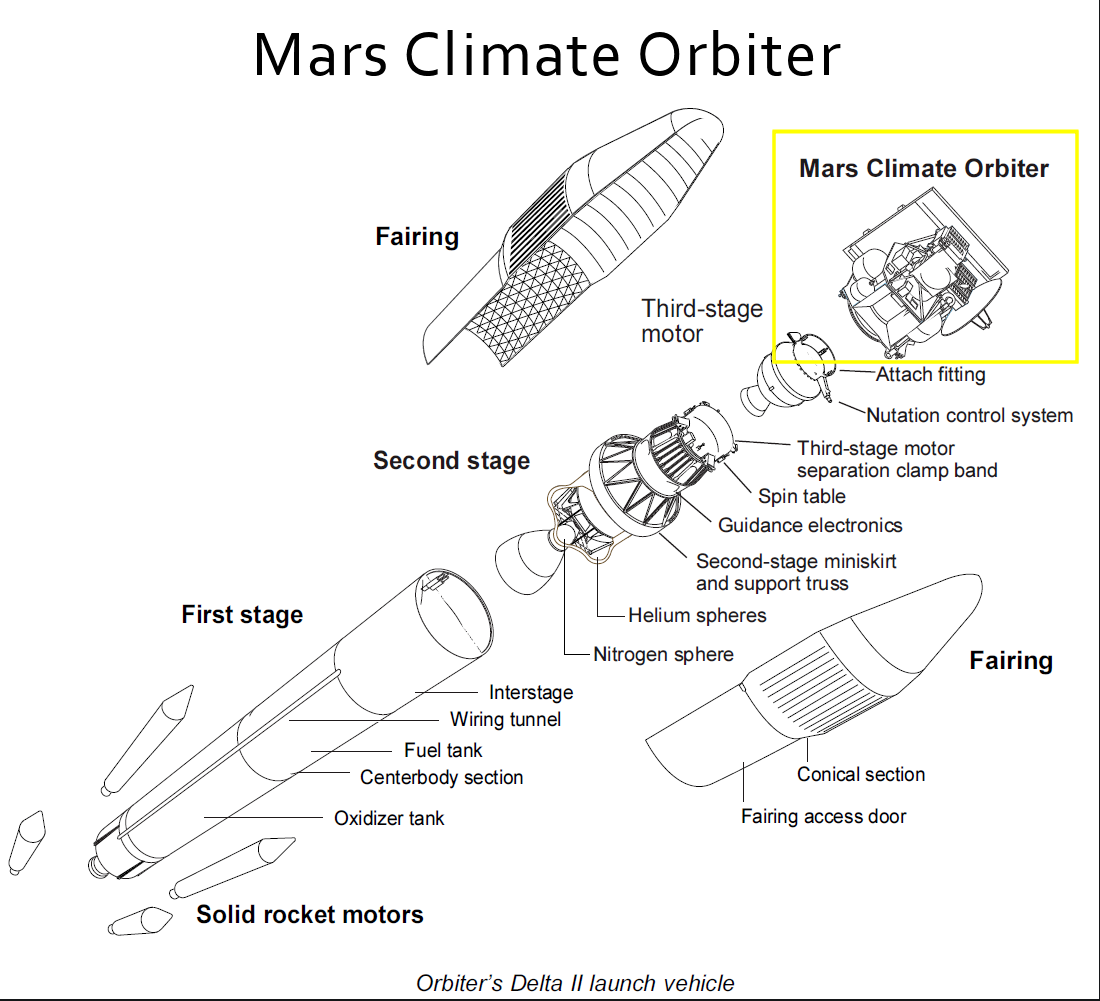

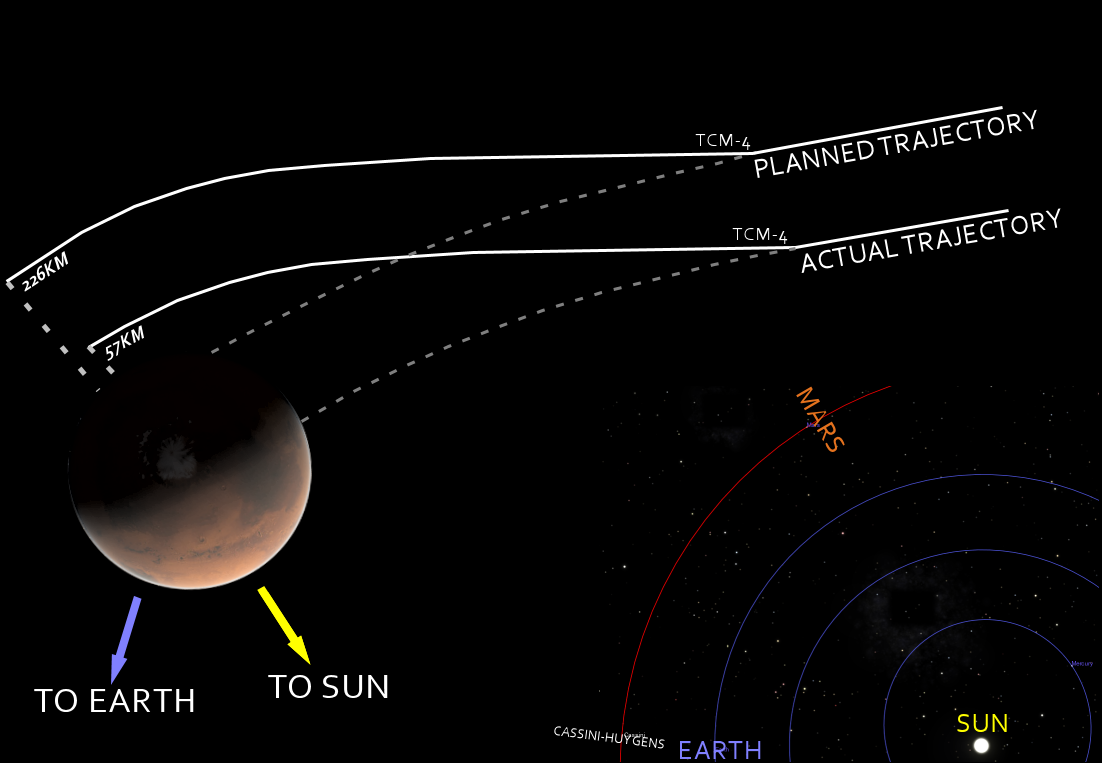

In September 1999, NASA’s $125 million Mars Climate Orbiter reached the red planet after a nine-month journey, only to vanish without a trace. The mission was declared a total loss. The investigation that followed uncovered a stunning cause: the spacecraft wasn’t lost to an engine explosion or a hardware malfunction, but to a simple, embarrassing mix-up in its ground control software.

The Root Cause: A Simple Mismatch in Units

The mission was a collaboration. The contractor, Lockheed Martin, built ground software that controlled the Mars Climate Orbiter’s thrusters, while NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) managed the navigation. The fatal flaw was born in the communication gap between them.

The Unit Mismatch (System Integration Error): Lockheed Martin’s software calculated thruster force in pound-force, but NASA’s software expected newtons.

\[\Large {1 \mathit{\ pound\ force} = 4.44822162 \mathit{\ newtons}}\]

How a Bug Became a Disaster: The Chain of Failures

- The Accumulating Error: Every calculation NASA made was off by a factor of 4.45. They thought they were making tiny corrections but were actually pushing the spacecraft further off course.

- Failure of “End-to-End” Testing: The teams never tested both software systems together. A simple integration test would have caught this immediately.

- Warnings Were Missed: Engineers noticed the drift but didn’t escalate it quickly enough. After 9 months, the error compounded until the orbiter was lost.

Conclusion: The entire mission was lost because of a simple unit conversion. It’s a lesson in the importance of thorough testing and clear communication.

These stories share a common thread: the most catastrophic failures often begin with the smallest and most “human” of errors. They weren’t caused by evil hackers or rogue AIs, but by simple oversights, flawed assumptions, and failures in communication. These events serve as a powerful reminder that the greatest challenge in software engineering isn’t just making things work. It’s anticipating and safely handling what happens when they inevitably go wrong.

They prove that functional code is only the starting point; the true measure of a system’s strength is how gracefully it handles its own inevitable flaws.

References & Further Learning

THERAC-25:

- Death and Denial: The Failure of the THERAC-25, A Medical Linear Accelerator

- History’s Worst Software Error - Youtube

- The Tragic Race Condition - Team Codereliant

The Patriot Missile:

Mars Climate Orbiter: